In our second part of this series, we are going to take a look at the Green Bay Packers’ variation on its base defense, the “Eagle.” This mostly highlights a shift in how the defensive linemen position themselves – what technique they play and which gaps they are responsible for. The Packers have been known to use this more than their “Okie” formation in an attempt to play to their linemen’s strengths.

In our second part of this series, we are going to take a look at the Green Bay Packers’ variation on its base defense, the “Eagle.” This mostly highlights a shift in how the defensive linemen position themselves – what technique they play and which gaps they are responsible for. The Packers have been known to use this more than their “Okie” formation in an attempt to play to their linemen’s strengths.

Explaining the Formation

Just like the Okie, this is a 3-4-4 formation generally used to counter offenses with two wide receivers or less. You’ll see it against potential running plays, but it’s also a little more equipped to attack and counter passing plays.

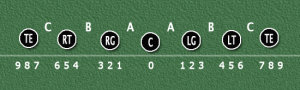

Before going into more detail, let’s quickly revisit our gap and technique diagram for the defense:

In the Eagle front, the nose tackle will still line up across from the center in a 0-technique, but he will “shade” himself towards the strong side shoulder. He will read the center and the ball on the snap and will be responsible for both of the A gaps.

The defensive end on the strong side of the formation will play the normal 5-technique, which is heads up over the tackle, yet his read will be the guard. Like the nose tackle, he remains a two-gap player. On the weak side of the formation, however, the other defensive end will play a 3-technique on the outside shoulder of the guard. The big change here is that this end can now become a one-gap player.

Cullen Jenkins used to be weak side end in this front, since it allowed him to shoot the B gap as a pass rusher. Dom Capers has since used B.J. Raji in this role, since he is a better one-gap than two-gap player. And as you will note in the example below, Jerel Worthy has also been called upon to play the weak side 3-technique in the Eagle.

By adding one-gap techniques into the front, the defensive lineman can also be used to “eat up” two offensive linemen. In both run and pass blitzing situations, this helps linebackers get past those otherwise occupied blockers.

It’s challenging to find a really good nose tackle in the NFL these days, and it’s even harder to find three defensive linemen who can consistently be two-gap players. The Eagle front helps to address this problem, since you can use a mixture of one-gap and two-gap assignments.

So when fans have criticized Ted Thompson for drafting players that “can’t play 5-technique,” their reproach is slightly unfounded. Players like Ryan Pickett are still essential to the defense, but Capers tends to use more Eagle than the traditional Okie in his 3-4 packages, so there are legitimate spots for strong 3-technique players. And as you will see in the nickel and dime analyses, the two-gapping becomes even less important.

The Eagle Defense in Action

Here is an interesting example of the Eagle defense. This is from Week 6 in 2012, when the Packers embarrassed the Houston Texans. It was the first play of the game, and the Texans were starting on their own 19-yard line.

Breaking Down the Play

The Houston Texans are a team known for their play action success. They have a strong running game built around Arian Foster and a big wide receiver in Andre Johnson who can work the deep field. So when they start the game using a 13 personnel grouping (1 RB–3 TE–1 WR), they’ve got some flexibility to run or throw the ball.

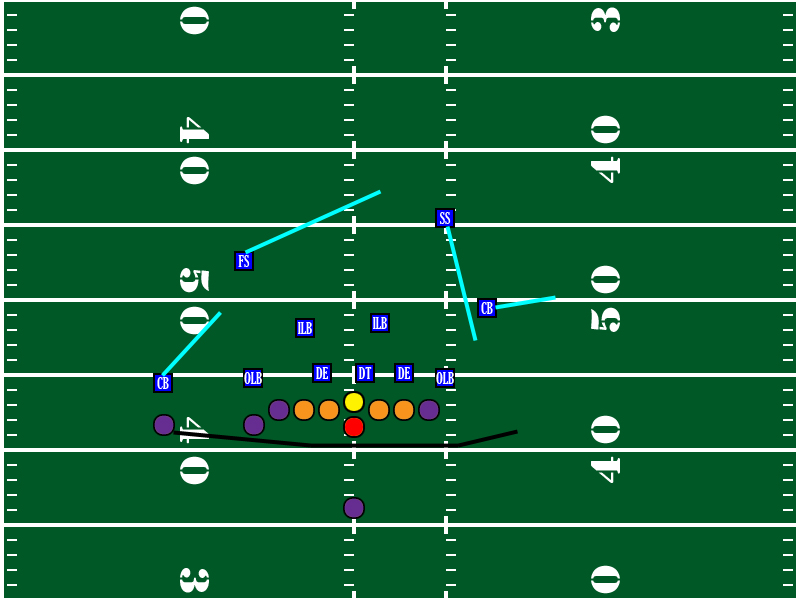

Dom Capers, in response to this, calls on his Eagle defense. Here is how the players initially line up:

As you can clearly see, the defensive linemen are not in a traditional Okie front. Jerel Worthy is playing the weak side end, lining up in a 3-technique off the left guard. Ryan Pickett is playing nose tackle, shaded to the strong side of the center. And C.J. Wilson is playing the strong side in a 5-technique across from the left tackle. Dom Capers has put them in their most natural positions using the Eagle, giving them the best chance to succeed.

One interesting thing to note is how the strong side of the offense is defined in this instance. Generally speaking, the strong side of the offense is identified by the presence of the tight end. In the case of this three tight end set, you could call the side with two tight ends the strong side, since it has more players. However, sometimes defenses will use the “wide side” of the field as the strong side. This could be the case here, though I’m not 100% certain.

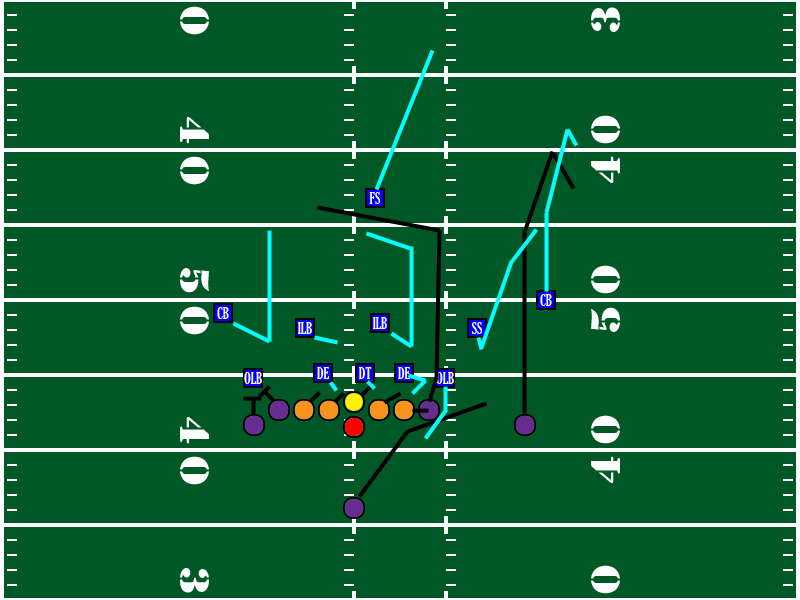

Perhaps it was film study and the tendencies of the Texans that caused the defense to declare the right side the strong side. Either way, it seemed to be the right call, as here’s what happens after the wide receiver motions and the secondary rotates their coverage:

As could have been expected, the Texans begin the game with a play action. The offensive line slides right in what initially looks to be a zone running play (something the Texans are very fond of), but they quickly engage the defense in pass blocking after the fake handoff.

The Packers have it all covered, though. The secondary does an excellent job shutting down the receivers, giving Matt Schaub nowhere to go with the ball. C.J. Wilson collapses his side of the pocket and closes in for the kill when Schaub tries to escape. Aside from the pass coverage, this pressure was all on Wilson’s ability to beat his man.

I also want you to go back to the video and watch what Ryan Pickett does, though. He accomplishes something very small but very significant. When the running back tries to leak into the flat for a checkdown, Pickett disengages from the center and disrupts the route of the back. It gives the defense just enough time to break down the pocket and eliminates Schaub’s last passing option. Clearly a heads-up play by a veteran lineman.

One final thing worth noting is how the Texans double-team Clay Matthews and Jerel Worthy on Scahub’s blind side. At first, I was curious as to why one of those tight ends didn’t break off into a passing route, but Schaub is really only reading the right side of the field. It also allows the offense to get two guys on each of the Packers’ best pass rushers (Matthews and Worthy). But as you would hope to see, defensive players need to take advantage of their one-on-one matchups when the offense has turned their focus elsewhere.

——————Chad Toporski, a Wisconsin native and current Pittsburgh resident, is a writer for AllGreenBayPackers.com. You can follow Chad on twitter at @ChadToporski

Follow @ChadToporski——————

Alright, I’ll risk asking a dumb question. It seems like this formation leaves the weak side C gap wide open, putting a lot of pressure on the weak side ILB. Am I missing something, or wouldn’t it make sense to audible to a run off the right tackle? I understand that every alignment has its weaknesses, but this one seems pretty glaring.

The example above might be a bit unconventional as far as the Eagle goes, because the “strong side” declaration by the defense wasn’t based on the balance of the line.

If you imagine a line with just one tight end, the “C” gap on the weak side is well taken care of by the outside linebacker, because he doesn’t have a tight end to worry about.

Something like this:

E T G C G TO D D D O

It also might have to do with what assignment Matthews ultimately has and what keys he was looking into. Ultimately, he decides to loop outside when he sees it’s a pass but, if he thinks it’s a run, he likely scrapes in to help the ILB

Ben, I’ll join you in this question. Seems to me an off-tackle run to the left leaves the offense with a numbers advantage.

In the example in the article, I would tend to agree. However, I’m not sure how much control Schaub had over the offensive calls and his available audibles.

Hey Al.

Potential post that could be explored.

http://thesidelineview.com/columns/nfl/metrics-breakdown-top-running-backs-tier-1

Wow! Does this say a few things about what Lacy can add to a below average line?

Again, nice work Chad. You’ve taken on a pretty difficult task here, mostly because when it comes to terminology there is no right or wrong. As I’m sure most of us know very well, a football term means whatever the team says it means.

I understand the basic concepts, but I really have no idea what terms the Packers use to describe those concepts. As you pointed out, some defenses might call the side with more players on it (usually – but not necessarily – because of the presence of the TE) the “strong” side, but other teams might call the wide side of the field “strong”. In some defenses, strong and weak means little more than right and left. The only way to know for sure what a certain team calls it is to have inside information. And I don’t.

In the end, it doesn’t matter, though. IMO, the purpose of the designation isn’t really to identify how the OFFENSE is aligned, but to identify how the DEFENSE is going to play it. And I think you’ve caught that issue pretty well. The 3-4 Eagle incorporates the idea of a “one gapping” end.

(One side note here: There is another, perhaps even more popular meaning for “3-4 Eagle defense.” For a lot of teams, 3-4 Eagle means that the nose tackle is replace by a linebacker who plays directly over center. Fritz Shurmur used this formation all the time, which our man Kevin Greene as his “nose backer”. It’s totally different from what your talking about, and just another example of how terminology means whatever a team says it means.)

I think there is another difficulty, and that is that teams can easily “flip” the defense like a mirror image. In other words, it isn’t ALWAYS the 3-technique on the weak side and the 5-technique on the strong side, but they can flip it around the other way if they want to, so long as everyone in the defensive huddle knows what’s going on. In effect, that is exactly what the Packers did here, since according to a more “standard” sort of terminology, Worthy is actually on the strong side, not the weak side.

One more thing: I chuckled a bit… I love “Big Grease”, but don’t think Pickett was showing great instincts bumping off the RB. I’m pretty sure Pickett thought he had the ball.

Kudos on the article.

Thanks, marpag.

That’s the one inherent flaw in football analysis from any angle – you don’t know exactly how the play was called, what adjustments were made, and why. Some plays are straight-forward, others are more complicated.

Thank, btw, for bringing up the Shurmur Eagle. I had come across that in some of my research, and it definitely intrigued me.

As for Pickett, I think you can make either case… but I didn’t consider what you suggested. Makes sense.

All I really remember about the “Shurmur Eagle” is that Greene was holy hell playing on the nose. Even though I think he played straight up, he was still one gapping, and because he was so much quicker than the center he pretty much had a “two-way go” – he could shoot the A gap on either side, and the O-line couldn’t double him because they didn’t know which side he would take. Couple that with the fact that coming from the nose is the shortest path to the ball, and you can see why it was so lethal.